I was sitting on this for few years now, using it as an example in a couple of seminar talks, but not really doing anything with it. It seems like a good candidate for a first post on my new blog.

Complex Domain Coloring

A long time ago I ran across a website created by Frank Farris and Jeffrey Hoffstein, that showed some awesome images of automorphic functions created using a method for visualizing complex functions of complex variable called Complex Domain Coloring. I immediately tried to create similar images, at the beginning using the GNU Image Manipulation Program (GIMP) and its MathMap plugin. Initially MathMap did not even have any support for complex numbers, and all calculations had to be done using reals, which made more complicated functions practically impossible to work with. Hans Lundmark was also interested in working with MathMap plugin, and he added a support for complex numbers, so we were able to create some pretty interesting images. Later I wrote few Python scripts that produced some pretty nice results, but were horribly written, and luckily, got lost in the cracks of time. I also used a nice S-lang script written by John Davis. I still have some old images created with GIMP, Python and S-Lang at my old website, unfortunately, I no longer have an access to update the site.

Couple years ago, when reading the AMS blog on math blogs, I came across a link to a

website that posted two or three images of

complex valued continued fraction approximations each day. At that time I was

just learning Julia, and decided that with its speed it would be a perfect tool

for generating such images. That resulted in a Jupyter notebook with some code

generating such images. While looking for it last month, I was not able to

find it. I now believe that I had it stored on juliabox.org, and when they

moved to a .com domain, I completely missed the transition period when you

could have your files moved over, and now they are gone. So it had to be

written again, and here it is.

Calculating continuing fractions

First we need to have some way to calculate convergents of continuing fractions. That is actually surprisingly easy: there is a simple doubly recursive formula that can be used.

Suppose we have a continuing fraction

A bit of symbol pushing reveals that its -th convergent can be written in the form

where both and satisfy the recursive formula

with initial values

Special example

If for and for , the recursive formula becomes

and is the -nd Fibonacci number, while is the -st Fibonacci number. The convergents of the continuing fraction

are the ratios of consecutive Fibonacci numbers, and converge to the golden ratio

Julia implementation

Our continuous fraction coefficients will be functions of a complex variable. We will also want to calculate the convergents for a whole array of complex numbers at once. Both of thee things are easy in Julia.

We want to find convergents of a continuous fraction

We can consider and functions of two variables: the index and a complex number :

We will first define a function drec that will implement the doubly recursive

formula. It will receive the coefficient functions and , with signatures

Int64 -> T -> T where in our case T will be some sort of complex number or

complex number array, two values of type T, representing the “initial values” and

, starting index that will be the index of the first calculated

value, and ending index that will be the index of the last calculated

value, one that will be returned. Finally, drec will receive as its last

argument a value of type T.

The function will use broadcasting versions of operators so it will allow T

to be an array.

function drec(a::Function, b::Function,

xₛ₋₂::T, xₛ₋₁::T, s::Int64,

e::Int64, z::T) where {T}

for i = s:e

(xₛ₋₂, xₛ₋₁) = (xₛ₋₁, a(i, z) .* xₛ₋₁ .+ b(i, z) .* xₛ₋₂)

end

return xₛ₋₁

end## drec (generic function with 1 method)Now we will use the doubly recursive formula to find both the numerator and the denominator of the -th convergent. Again, all operators broadcast.

function contfrac(a::Function, b::Function, k::Int64, z)

n0 = a(0, z)

n1 = a(1, z) .* n0 .+ b(1, z)

d1 = a(1, z)

d2 = a(2, z) .* d1 .+ b(2, z)

return drec(a, b, n0, n1, 2, k, z) ./ drec(a, b, d1, d2, 3, k, z)

end## contfrac (generic function with 1 method)Generating images

We will start by creating a array of complex numbers representing an area of complex plane (this should really be made more flexible, but at this moment I just want to see some quick pictures).

function plane(x0, y0, x1, y1)

xscale = (x1 - x0)/500

yscale = (y1 - y0)/500

return [(x0 + xscale*i) + (y1 - yscale*j)im for j=0:500, i=0:500]

end## plane (generic function with 1 method)We will feed this region as an input to our continuing fraction approximation to get an array of complex values. Then we convert this array into an image.

Mapping complex numbers to colors

Now we need some way to turn an array of complex numbers into an array of

colors. For that we will need the Images module.

using ImagesThere are infinitely many ways of mapping the complex plane into a color space. We will try the following three:

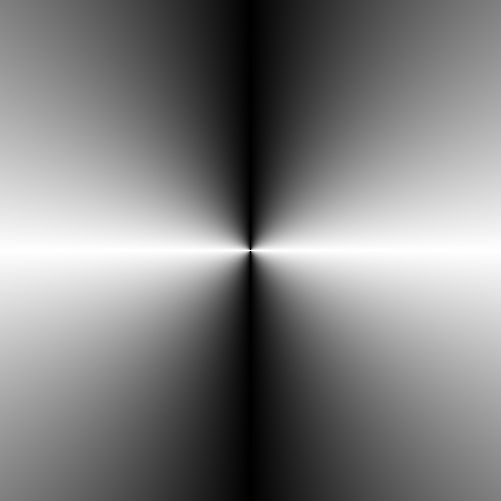

A simple gray scale mapping

In this mapping the color associated to a complex number is determined purely by its argument, in such a way that real axis will be white and imaginary axis black. This is, as far as I can tell, the mapping used on the website that came up with the images we are trying to imitate.

function GrayReIm(z)

shade = 2 .* abs.(abs.(angle.(z)) ./ pi .- 0.5)

return Gray.(shade)

end## GrayReIm (generic function with 1 method)

colors = GrayReIm(plane(-1.0, -1.0, 1.0, 1.0));This will produce the following coloring of the complex plane:

gray coloring

Map argument to hue

Just like the previous mapping, the color of a number is determined purely by its argument. This time we map the argument to the hue, while keeping the saturation and lightness maximum.

function ArgHue(z)

hue = ((angle.(z)) ./ π .+ 1) .* 180

return HSV.(hue, 1, 1)

end## ArgHue (generic function with 1 method)

colors = ArgHue(plane(-1.0, -1.0, 1.0, 1.0));This will produce the following coloring of the complex plane:

hue coloring

Map complex numbers to HSV colors

This is not just one mapping, instead it is a function that generate mappings.

The hue is determined by the argument of the complex number, just like with the

ArgHue mapping above, but this time the saturation and lightness are

calculated from the modulus of the complex number. The calculation is

influenced by two parameters, f1 and f2.

function CompHSV(f1, f2)

function f(z)

hue = ((angle.(z)) ./ π .+ 1) .* 180

s = 2 .* atan.(( abs.(f1 .* z))) ./ π

v = 1 .- 2 .* atan.(( abs.(f2 .* z))) ./ π

return HSV.(hue, s, v)

end

return f

end## CompHSV (generic function with 1 method)

colors = CompHSV(2.0, 0.5)(3 .* plane(-1.0, -1.0, 1.0, 1.0));This will produce the following coloring of the complex plane:

hsv coloring

Generating the actual plot

The following function puts it all together. It receives the corners of the plotted region, the coefficient functions and , the number indicating which convergent to calculate, and a coloring function. It will return the resulting image.

function plotCF(x0, y0, x1, y1, a::Function, b::Function, k::Int64,

coloring::Function)

z = plane(x0, y0, x1, y1)

image = contfrac(a, b, k, z)

return coloring(image)

end## plotCF (generic function with 1 method)Examples

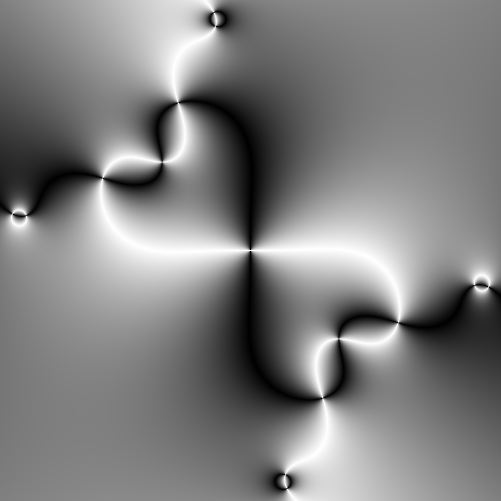

Image no 17

function a(i::Int64, z)

if i == 0

return zero(z)

end

return z .* cis(π * i/2)

end## a (generic function with 1 method)

function b(i::Int64, z)

return zero(z) .+ i

end## b (generic function with 1 method)

img = plotCF(-2.0, -2.0, 2.0, 2.0, a, b, 100, GrayReIm);

Image number 17

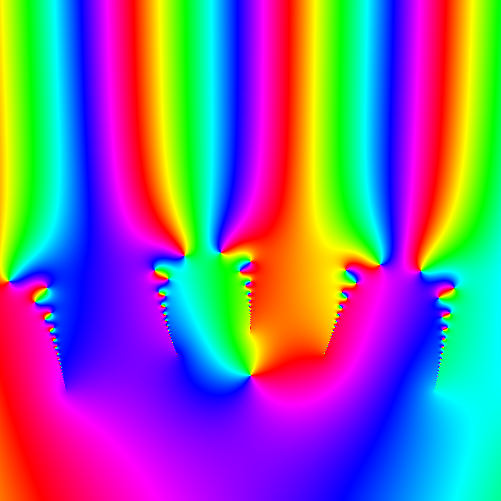

Image no 255

function a1(i::Int64, z)

if i == 0

return zero(z)

end

return cis.(π .* z)

end## a1 (generic function with 1 method)

function b1(i::Int64, z)

return (-1)^i .* z

end## b1 (generic function with 1 method)

img = plotCF(-1.0, -.5, 1.0, 1.5, a1, b1, 100, ArgHue);

Image number 255

Image no 246

function a2(i::Int64, z)

if i == 0

return zero(z)

end

return i * cis.(-π * i/2) .* z

end## a2 (generic function with 1 method)

function b2(i::Int64, z)

return cis(-π*i/2) * i .+ z

end## b2 (generic function with 1 method)

img = plotCF(-1.0, -.5, 1.0, 1.5, a2, b2, 100, CompHSV(2.0, 0.5));

Image number 246

Problems, notes, etc.

One problem with these images is that they are not images of continuing fractions. At best they are images of approximations of these fractions, but even that is not necessarily true. What we really visualize here are specific convergents of the continuing fractions, without actually making any claims of convergence or quality of approximation.

Even in cases where the continuing fraction converges, the method we use for calculating the convergents is of limited use: the numerator and denominator sequences may diverge, and so trying to improve our approximation of the continuing fraction may result in a floating point overflow.

As far the Julia code goes, you can see that it is all written in vectorized form, with almost mo explicit loops. I find that style easier to both write and read, especially when coding math, and in most interpreted languages, such code is also faster. In Julia, however, well written loops are actually faster than vectorized code. It would be interesting to see how much speed up could be gain by de-vectorizing the code.